Talking about how bad the government is all the time can be depressing, and wearying. One of the joys in reading Bourbon for Breakfast and Its a Jeten's World by Jeffery Tucker is that much of those two books are about the marvels of private interactions and private enterprise, when it is left alone by the government.

Read them and enjoy a fun way of understanding what is wrong with the world.

Buy them, or read them for free, here.

"When you talk about liberty, smile." - Milton Freidman

I pledge allegiance to the supercomputer of the United States of Data Mining. And to the dictatorship for which it stands, one nation, under Obama, unencryptable, with tyranny and injustice for all.

Showing posts with label Bourbon for Breakfast. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Bourbon for Breakfast. Show all posts

Monday, January 7, 2013

Monday, December 17, 2012

Links!

Also...

Links!

Dr. Tim says we are all at least half libertarians already, why not become complete libertarians? Liberty is what has made us more prosperous than anyone, anywhere, at any time.

excerpt:

excerpt:

Banning guns may not be the direct cause of more murders, but more murders do happen where guns are banned.

Katie Pavlich says:"New data out from the UK, where guns are banned, shows gun crime has soared by 35 percent."

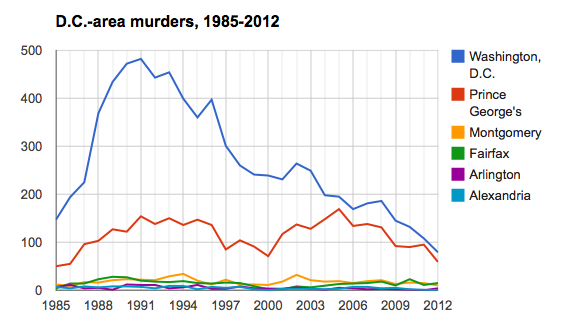

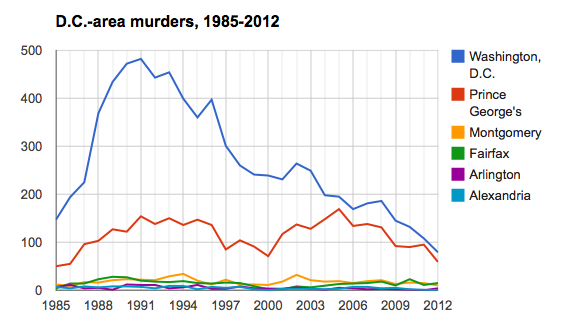

The following chart shows the number murders in each city in the Washington D.C. area. Which city, do you suppose, is the only one that banned handguns?

Dana Loesch comments on the CT shooting.

excerpts:

Plus there are links to good gun stories. (at the bottom of the page)

Jeffery Tucker, my favorite author and who's website is at the top of my list of blog links for a reason, says that, despite the Fed's insistence to the contrary, the Fed's activities will hurt, not help, our unemployed.

excerpt:

"Oh no!" the bad Syrians will say, "Tough and scary By The Way I served in Vietnam is here to end evil and save the day! Whatever shall we do!?!"

[Note to my liberal readers: The previous two paragraphs are sarcasm. Sarcasm is when someone says one thing but means the opposite.]

Links!

Dr. Tim says we are all at least half libertarians already, why not become complete libertarians? Liberty is what has made us more prosperous than anyone, anywhere, at any time.

excerpt:

Liberty’s first virtue is its practicality. Liberty immunizes the general population from the tragic mistakes of its individual members. When two people exchange in bad faith, those two people alone suffer the consequences. Unless, of course, those two people just happen to be John Boehner and Barack Obama - then the innocent victims number in the hundreds of millions.

The idea itself is absurd; why should two men you have never met negotiate how much of your labor they will keep for their own purposes? What if they compromise on all of it? Would you celebrate the spirit of bipartisanship and breathe a sigh of relief that a crisis has been averted? Will you be happy that Washington is working again? Does gridlock still seem like such an awful thing?For that matter, can you even describe the crisis they are trying to avert without using the word “cliff”? It is a fiscal curb, crack in the driveway, a chalk line.

They are niggling over the last half trillion as if the first $100 trillion of unfunded liabilities doesn’t matter. If Mr. Obama and Mr. Boehner would decide to quit stalling and take all of the nation's wealth, we would finally be equal. That should make many people happy, as equality - not freedom - is the progressive's perverted idea of justice.

Equality of outcome has a price, and that price is everything.

The relevant question is not which of those two men will convince the Beltway paparazzi that the other guy blinked: it is how much government do we need? We can answer it in two minutes right here: Democrats, write down how much of your own income you would have given to George W.Bush if he could spend it any way he chose; Republicans, do the same with President Obama in mind.

What did you decide? 5%, maybe less? There you go – nearly everyone is already half-libertarian; now just keep both the left hand and right hand out of your wallet - and your school, your work, your bedroom, your gun rack, your church, your charity, your emails, and your stash - and you will complete the journey.

Francis Begbe writes the best description of the CT shooting that I have read anywhere.Alas, the current President does not read Moment Of Clarity, he does not seek consensus on such trivial matters, and he does not regard the Constitution – wisely written to protect us from guys like him - as particularly relevant to his ambitions. He is hell-bent on raising income tax rates on the wealthiest Americans, and the Republicans appear to be ready to do what they do best – cave.

excerpt:

So, just another few things. First, events like these cannot be predicted. They are Black Swans in the truest sense, although negative Black Swans are more likely to occur than positive Black Swans. With youth unemployment as high as it is, with hypergamy being what it is, with obfuscating leftie Boomer mentality pirulating every aspect of society, all exacerbated by a mental condition, that is what makes people just give up. The foot on the face of the beta male. Work on that. This wasn't a suicide neither, this was an act of desperation, an act seen though the lens of a horrible, crushing future. Second, murders like this don't occur when someone "snaps". They are usually meticulously planned, months and months in advance. Lanza was long gone before yesterday, long gone. Was something going on here with the mother we don't know about as well?One problem with Francis' post is this: "obvious disclaimer, I'm not saying that gun restriction causes murders"

Banning guns may not be the direct cause of more murders, but more murders do happen where guns are banned.

Katie Pavlich says:

The following chart shows the number murders in each city in the Washington D.C. area. Which city, do you suppose, is the only one that banned handguns?

Dana Loesch comments on the CT shooting.

excerpts:

Where have these mass tragedies occurred? Virginia Tech. Aurora, Colorado. Schools, the majority of them. What do these locations have in common? They are designated “gun-free” zones. Are progressives unable to recognize that their gun control was already in place? Guns were already forbidden? The only solution left is “confiscation,” which goes beyond what they imply by “control.” I would like to hear it explained how a gun-free school zone, in a state with some of the most stringent gun control laws in the country, would have prevented the actions of a man whose intent was not following the law that day?another excerpt:

From Glenn Reynolds in USA Today:excerpt:

One of the interesting characteristics of mass shootings is that they generally occur in places where firearms are banned: malls, schools, etc. That was the finding of a famous 1999 study by John Lott of the University of Maryland and William Landes of the University of Chicago, and it appears to have been borne out by experience since then as well.

I’d like for the left to explain how it is people are dying from gun shots in Chicago when the city explicitly banned them?excerpt:

The NSC estimates that in 1995, firearm accidents accounted for 1.5% of fatal accidents. Larger percentages of fatal accidents were accounted for by motor vehicle accidents (47%), falls (13.5%), poisonings (11.4%), drowning (4.8%), fires (4.4%), and choking on an ingested object (3.0%).Ban gravity! Ban Poison! Ban water! Ban fire! Ban choking!

Plus there are links to good gun stories. (at the bottom of the page)

Jeffery Tucker, my favorite author and who's website is at the top of my list of blog links for a reason, says that, despite the Fed's insistence to the contrary, the Fed's activities will hurt, not help, our unemployed.

excerpt:

Ben Bernanke began his press conference with a touching tribute to the unemployed. Oh, how he cares! And so deeply! His description of the problem was accurate enough. But then out came the smoke and mirrors.Good news! John "By The Way I Served in Vietnam" Kerry is going to be our new Secretary of State! Don't you feel safer? How soon do you suppose that quibble in Syria will get cleaned up once By The Way I Served in Vietnam arrives on scene?

Bernanke said that to remedy the unemployment problem, he will continue the Fed’s program of asset purchases. Specifically, the Fed will continue to buy and hold mortgage-backed securities (yes, they are still sloshing around the banking system) and Treasury securities — $40 billion-plus per month. Plus, he will keep the federal funds rates at near zero.

The great change, he said, is the intense focus on the policy objective of unemployment. The committee sees no inflation threat, so it might as well turn its attention to the labor markets. The Fed loves the unemployed, you see, and wants to help them.

But here’s the disconnect. What the devil does buying bad debt from zombie banks have to do with getting people jobs? The relationship between assets purchases and policy goals is murky at best.

“I need a job, so I hope the Fed buys more bad mortgage debt” — said no unemployed person ever.

"Oh no!" the bad Syrians will say, "Tough and scary By The Way I served in Vietnam is here to end evil and save the day! Whatever shall we do!?!"

[Note to my liberal readers: The previous two paragraphs are sarcasm. Sarcasm is when someone says one thing but means the opposite.]

Monday, December 10, 2012

The Trouble With Child Labor Laws

Bourbon for Breakfast by Jeffery Tucker

Chapter 16

Let’s say you want your computer fixed or your software explained.

You can shell out big bucks to the Geek Squad, or you can ask—but

you can’t hire—a typical teenager, or even a preteen. Their experience

with computers and the online world is vastly superior to that of most

people over the age of 30. From the point of view of online technology, it is

the young who rule. And yet they are professionally powerless: they are forbidden

by law from earning wages from their expertise.

Might these folks have something to offer the workplace? And might

the young benefit from a bit of early work experience, too? Perhaps—but

we’ll never know, thanks to antiquated federal, state, and local laws that

make it a crime to hire a kid.

Pop culture accepts these laws as a normal part of national life, a means

to forestall a Dickensian nightmare of sweat shops and the capitalist exploitation

of children. It’s time we rid ourselves of images of children tied to rug

looms in the developing world. The kids I’m talking about are one of the

most courted of all consumer sectors. Society wants them to consume, but

law forbids them to produce.

You might be surprised to know that the laws against “child labor” do

not date from the 18th century. Indeed, the national law against child labor

didn’t pass until the Great Depression—in 1938, with the Fair Labor Standards

Act. It was the same law that gave us a minimum wage and defined

what constitutes full-time and part-time work. It was a handy way to raise

wages and lower the unemployment rate: simply define whole sectors of the

potential workforce as unemployable.

By the time this legislation passed, however, it was mostly a symbol,

a classic case of Washington chasing a trend in order to take credit for it.

Youth labor was expected in the 17th and 18th centuries—even welcome,

since remunerative work opportunities were newly present. But as prosperity

grew with the advance of commerce, more kids left the workforce. By

1930, only 6.4 percent of kids between the ages of 10 and 15 were actually

employed, and three out of four of those were in agriculture.

In wealthier, urban, industrialized areas, child labor was largely gone, as

more and more kids were being schooled. Cultural factors were important

here, but the most important consideration was economic. More developed

economies permit parents to “purchase” their children’s education out of

the family’s surplus income—if only by foregoing what would otherwise be

their earnings.

The law itself, then, forestalled no nightmare, nor did it impose one. In

those days, there was rising confidence that education was the key to saving

the youth of America. Stay in school, get a degree or two, and you would

be fixed up for life. Of course, that was before academic standards slipped

further and further, and schools themselves began to function as a national

child-sitting service. Today, we are far more likely to recognize the contribution

that disciplined work makes to the formation of character.

And yet we are stuck with these laws, which are incredibly complicated

once you factor in all state and local variations. Kids under the age of 16

are forbidden to earn income in remunerative employment outside a family

business. If dad is a blacksmith, you can learn to pound iron with the best of

’em. But if dad works for a law firm, you are out of luck.

From the outset, federal law made exceptions for kid movie stars and

performers. Why? It probably has something to do with how Shirley Temple

led box-office receipts from 1934–1938. She was one of the highest earning

stars of the period.

If you are 14 or 15, you can ask your public school for a waiver and

work a limited number of hours when school is not in session. And if you

are in private school or home school, you must go ask your local Social Service

Agency—not exactly the most welcoming bunch. The public school

itself is also permitted to run work programs.

This point about approved labor is an interesting one, if you think about

it. The government doesn’t seem to mind so much if a kid spends all nonschool

hours away from the home, family, and church, but it forbids them

from engaging in private-sector work during the time when they would otherwise

be in public schools drinking from the well of civic culture.

A legal exemption is also made for delivering newspapers, as if bicycles

rather than cars were still the norm for this activity.

Here is another strange exemption: “youth working at home in the

making of wreaths composed of natural holly, pine, cedar, or other evergreens

(including the harvesting of the evergreens).” Perhaps the wreath

lobby was more powerful during the Great Depression than in our own

time?

Oh, and there is one final exemption, as incredible as this may be: federal

law allows states to allow kids to work for a state or local government at

any age, and there are no hourly restrictions. Virginia, for example, allows

this.

The exceptions cut against the dominant theory of the laws that it is

somehow evil to “commodify” the labor of kids. If it is wonderful to be a

child movie star, congressional page, or home-based wreath maker, why is

it wrong to be a teenage software fixer, a grocery bagger, or ice-cream scooper?

It makes no sense.

Once you get past the exceptions, the bottom line is clear: full-time

work in the private sector, for hours of their own choosing, is permitted

only to those “children” who are 18 and older—by which time a child has

already passed the age when he can be influenced toward a solid work ethic.

What is lost in the bargain? Kids no longer have the choice to work for

money. Parents who believe that their children would benefit from the experience

are at a loss. Consumers who would today benefit from our teens’

technological know-how have no commercial way to do so. Kids have been

forcibly excluded from the matrix of exchange.

There is a social-cultural point, too. Employers will tell you that most

kids coming out of college are radically unprepared for a regular job. It’s

not so much that they lack skills or that they can’t be trained; it’s that they

don’t understand what it means to serve others in a workplace setting. They

resent being told what to do, tend not to follow through, and work by the

clock instead of the task. In other words, they are not socialized into how

the labor market works. Indeed, if we perceive a culture of sloth, irresponsibility,

and entitlement among today’s young, perhaps we ought to look here

for a contributing factor.

The law is rarely questioned today. But it is a fact that child-labor laws

didn’t come about easily. It took more than a hundred years of wrangling.

The first advocates of keeping kids out of factories were women’s labor

unions, who didn’t appreciate the low-wage competition. And true to form,

not consist of mining companies looking for cheap labor, but rather parents

and clergy alarmed that a law against child labor would be a blow against

freedom. They predicted that it would amount to the nationalization of

children, which is to say that the government rather than the parents or the

child would emerge as the final authority and locus of decision-making.

To give you a flavor of the opposition, consider this funny “Beatitude”

read by Congressman Fritz G. Lanham of Texas on the U.S. House floor in

1924, as a point of opposition to a child-labor ban then being considered:

blow against the freedom to work and a boost in government authority over

the family. The political class thinks nothing of legislating on behalf of “the

children,” as if they are the first owners of all kids. Child-labor laws were the

first big step in this direction, and the rest follows. If the state can dictate to

parents and kids the terms under which teens can be paid, there is essentially

nothing they cannot control. There is no sense in arguing about the

details of the law. The critical question concerns the locus of decision-making:

family or state? Private markets or the public sector?

In so many ways, child-labor laws are an anachronism. There is no

sense speaking of exploitation, as if this were the early years of the industrial revolution.

Kids as young as 10 can surely contribute their labor in some

tasks in ways that would help them come to grips with the relationship

between work and reward. They will better learn to respect private forms of

social authority outside the home. They will come to understand that some

things are expected of them in life. And after they finish college and enter

the workforce, it won’t come as such a shock the first time they are asked to

do something that may not be their first choice.

We know the glorious lessons that are imparted from productive work.

What lesson do we impart with child-labor laws? We establish early on who

is in charge: not individuals, not parents, but the state. We tell the youth

that they are better off being mall rats than fruitful workers. We tell them

that they have nothing to offer society until they are 18 or so. We convey

the impression that work is a form of exploitation from which they must be

protected. We drive a huge social wedge between parents and children and

lead kids to believe that they have nothing to learn from their parents’ experience.

We rob them of what might otherwise be the most valuable early

experiences of their young adulthood.

In the end, the most compelling case for getting rid of child-labor laws

comes down to one central issue: the freedom to make a choice. Those who

think young teens should do nothing but languish in classrooms in the day

and play Wii at night will be no worse off. But those who see that remunerative

work is great experience for everyone will cheer to see this antique

regulation toppled. Maybe then the kids of America can put their computer

skills to use doing more than playing World of Warcraft.

Chapter 16

Let’s say you want your computer fixed or your software explained.

You can shell out big bucks to the Geek Squad, or you can ask—but

you can’t hire—a typical teenager, or even a preteen. Their experience

with computers and the online world is vastly superior to that of most

people over the age of 30. From the point of view of online technology, it is

the young who rule. And yet they are professionally powerless: they are forbidden

by law from earning wages from their expertise.

Might these folks have something to offer the workplace? And might

the young benefit from a bit of early work experience, too? Perhaps—but

we’ll never know, thanks to antiquated federal, state, and local laws that

make it a crime to hire a kid.

Pop culture accepts these laws as a normal part of national life, a means

to forestall a Dickensian nightmare of sweat shops and the capitalist exploitation

of children. It’s time we rid ourselves of images of children tied to rug

looms in the developing world. The kids I’m talking about are one of the

most courted of all consumer sectors. Society wants them to consume, but

law forbids them to produce.

You might be surprised to know that the laws against “child labor” do

not date from the 18th century. Indeed, the national law against child labor

didn’t pass until the Great Depression—in 1938, with the Fair Labor Standards

Act. It was the same law that gave us a minimum wage and defined

what constitutes full-time and part-time work. It was a handy way to raise

wages and lower the unemployment rate: simply define whole sectors of the

potential workforce as unemployable.

By the time this legislation passed, however, it was mostly a symbol,

a classic case of Washington chasing a trend in order to take credit for it.

Youth labor was expected in the 17th and 18th centuries—even welcome,

since remunerative work opportunities were newly present. But as prosperity

grew with the advance of commerce, more kids left the workforce. By

1930, only 6.4 percent of kids between the ages of 10 and 15 were actually

employed, and three out of four of those were in agriculture.

In wealthier, urban, industrialized areas, child labor was largely gone, as

more and more kids were being schooled. Cultural factors were important

here, but the most important consideration was economic. More developed

economies permit parents to “purchase” their children’s education out of

the family’s surplus income—if only by foregoing what would otherwise be

their earnings.

The law itself, then, forestalled no nightmare, nor did it impose one. In

those days, there was rising confidence that education was the key to saving

the youth of America. Stay in school, get a degree or two, and you would

be fixed up for life. Of course, that was before academic standards slipped

further and further, and schools themselves began to function as a national

child-sitting service. Today, we are far more likely to recognize the contribution

that disciplined work makes to the formation of character.

And yet we are stuck with these laws, which are incredibly complicated

once you factor in all state and local variations. Kids under the age of 16

are forbidden to earn income in remunerative employment outside a family

business. If dad is a blacksmith, you can learn to pound iron with the best of

’em. But if dad works for a law firm, you are out of luck.

From the outset, federal law made exceptions for kid movie stars and

performers. Why? It probably has something to do with how Shirley Temple

led box-office receipts from 1934–1938. She was one of the highest earning

stars of the period.

If you are 14 or 15, you can ask your public school for a waiver and

work a limited number of hours when school is not in session. And if you

are in private school or home school, you must go ask your local Social Service

Agency—not exactly the most welcoming bunch. The public school

itself is also permitted to run work programs.

This point about approved labor is an interesting one, if you think about

it. The government doesn’t seem to mind so much if a kid spends all nonschool

hours away from the home, family, and church, but it forbids them

from engaging in private-sector work during the time when they would otherwise

be in public schools drinking from the well of civic culture.

A legal exemption is also made for delivering newspapers, as if bicycles

rather than cars were still the norm for this activity.

Here is another strange exemption: “youth working at home in the

making of wreaths composed of natural holly, pine, cedar, or other evergreens

(including the harvesting of the evergreens).” Perhaps the wreath

lobby was more powerful during the Great Depression than in our own

time?

Oh, and there is one final exemption, as incredible as this may be: federal

law allows states to allow kids to work for a state or local government at

any age, and there are no hourly restrictions. Virginia, for example, allows

this.

The exceptions cut against the dominant theory of the laws that it is

somehow evil to “commodify” the labor of kids. If it is wonderful to be a

child movie star, congressional page, or home-based wreath maker, why is

it wrong to be a teenage software fixer, a grocery bagger, or ice-cream scooper?

It makes no sense.

Once you get past the exceptions, the bottom line is clear: full-time

work in the private sector, for hours of their own choosing, is permitted

only to those “children” who are 18 and older—by which time a child has

already passed the age when he can be influenced toward a solid work ethic.

What is lost in the bargain? Kids no longer have the choice to work for

money. Parents who believe that their children would benefit from the experience

are at a loss. Consumers who would today benefit from our teens’

technological know-how have no commercial way to do so. Kids have been

forcibly excluded from the matrix of exchange.

There is a social-cultural point, too. Employers will tell you that most

kids coming out of college are radically unprepared for a regular job. It’s

not so much that they lack skills or that they can’t be trained; it’s that they

don’t understand what it means to serve others in a workplace setting. They

resent being told what to do, tend not to follow through, and work by the

clock instead of the task. In other words, they are not socialized into how

the labor market works. Indeed, if we perceive a culture of sloth, irresponsibility,

and entitlement among today’s young, perhaps we ought to look here

for a contributing factor.

The law is rarely questioned today. But it is a fact that child-labor laws

didn’t come about easily. It took more than a hundred years of wrangling.

The first advocates of keeping kids out of factories were women’s labor

unions, who didn’t appreciate the low-wage competition. And true to form,

not consist of mining companies looking for cheap labor, but rather parents

and clergy alarmed that a law against child labor would be a blow against

freedom. They predicted that it would amount to the nationalization of

children, which is to say that the government rather than the parents or the

child would emerge as the final authority and locus of decision-making.

To give you a flavor of the opposition, consider this funny “Beatitude”

read by Congressman Fritz G. Lanham of Texas on the U.S. House floor in

1924, as a point of opposition to a child-labor ban then being considered:

Consider the Federal agent in the field; he toils not, nor

does he spin; and yet I say unto you that even Solomon in

all his populous household was not arrayed with powers

like one of these.

Children, obey your agents from Washington, for this is

right.

Honor thy father and thy mother, for the Government has

created them but a little lower than the Federal agent. Love,

honor, and disobey them.

Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, tell it to thy father and

mother and let them do it.

Six days shalt thou do all thy rest, and on the seventh day

thy parents shall rest with thee.

Go to the bureau officer, thou sluggard; consider his ways

and be idle.

Toil, thou farmer’s wife; thou shalt have no servant in thy

house, nor let thy children help thee.

And all thy children shall be taught of the Federal agent,

and great shall be the peace of thy children.

Thy children shall rise up and call the Federal agentIn every way, the opponents were right. Child-labor laws were and are a

blessed.

blow against the freedom to work and a boost in government authority over

the family. The political class thinks nothing of legislating on behalf of “the

children,” as if they are the first owners of all kids. Child-labor laws were the

first big step in this direction, and the rest follows. If the state can dictate to

parents and kids the terms under which teens can be paid, there is essentially

nothing they cannot control. There is no sense in arguing about the

details of the law. The critical question concerns the locus of decision-making:

family or state? Private markets or the public sector?

In so many ways, child-labor laws are an anachronism. There is no

sense speaking of exploitation, as if this were the early years of the industrial revolution.

Kids as young as 10 can surely contribute their labor in some

tasks in ways that would help them come to grips with the relationship

between work and reward. They will better learn to respect private forms of

social authority outside the home. They will come to understand that some

things are expected of them in life. And after they finish college and enter

the workforce, it won’t come as such a shock the first time they are asked to

do something that may not be their first choice.

We know the glorious lessons that are imparted from productive work.

What lesson do we impart with child-labor laws? We establish early on who

is in charge: not individuals, not parents, but the state. We tell the youth

that they are better off being mall rats than fruitful workers. We tell them

that they have nothing to offer society until they are 18 or so. We convey

the impression that work is a form of exploitation from which they must be

protected. We drive a huge social wedge between parents and children and

lead kids to believe that they have nothing to learn from their parents’ experience.

We rob them of what might otherwise be the most valuable early

experiences of their young adulthood.

In the end, the most compelling case for getting rid of child-labor laws

comes down to one central issue: the freedom to make a choice. Those who

think young teens should do nothing but languish in classrooms in the day

and play Wii at night will be no worse off. But those who see that remunerative

work is great experience for everyone will cheer to see this antique

regulation toppled. Maybe then the kids of America can put their computer

skills to use doing more than playing World of Warcraft.

Friday, November 16, 2012

Crush the Sprinkler Guild

from Jeffery Tucker's Bourbon for Breakfast (Chapter 6)

I suspected as much! What the lady at Home Depot called the “sprinkler

repair cult” is an emerging guild seeking privileges and regulations

from the government. That means a supply restriction, high prices, or

another do-it-yourself project. But there is a way around it.

I first began to smell a rat when the automatic irrigation system on my

front yard needed work but I had unusual struggles in trying to find a repair

guy.

The first place I called informed me that they could accept no more clients.

Clients? I just wanted a new sprinkler thing, for goodness sake. I don’t

want to be a client; I want to be a customer. Is there no one who can put on

a new sprayer or stick a screwdriver in there or whatever it needs?

Nope, all full.

The next call was not returned.

The next call ended with the person on the line fearfully saying that

they do landscaping but will have nothing to do with sprinklers or “automated

irrigation systems.” Umm, ok.

The next call seemed more promising. The secretary said they had an

opening on the schedule in three weeks. Three weeks? In that period of

time, my yard will be the color of a brown paper bag.

The next call failed. And the next one. And the next. Finally I was back

to the off-putting secretary. I made the appointment but the guy never came.

Fortunately, in the meantime, a good rain came, and then at regular intervals

for the whole season, and I was spared having to deal with this strangely

maddening situation.

Why all the fuss? We aren’t talking brain surgery here. These are sprinklers,

little spray nozzles connected to tubes connected to a water supply.

Why was everyone so touchy about the subject?

Why did all the power seem to be in their hands, and none in mine?

Must I crawl and beg?

Above all, I wonder why, with most all lawns in new subdivisions sporting

these little things, why oh why are the people who repair them in such

sort supply?

Little did I know that I had stumbled onto the real existence of a most

peculiar thing in our otherwise highly competitive economy: a guild.

It had all the earmarks. If you want your nails buffed, there are thousand

people in town who stand ready. If you want someone to make you

dinner, you can take your pick among a thousand restaurants. If you want to

buy a beer, you can barely go a block without bumping into a merchant who

is glad to sell you one. None of that is true with sprinkler repair.

What does a guild do? It attempts to restrict service. And why? To keep

the price as high as possible. And how? By admitting only specialists, or

supposed specialists, to the ranks of service providers, usually through the

creation of some strange but largely artificial system of exams or payments

or whatever.

Guilds don’t last in a free market. No one can blame producers for trying

to pull it off. But they must always deal with defectors. Even the prospects

of defectors can cause people who might not otherwise defect, to turn

and attempt to beat others to the punch.

There is just no keeping a producer clique together for long when profits

are at stake.

There is also the problem that temporarily successful guilds face: high

profits attract new entrants into the field. They must either join the guild or

go their own way. This creates an economically unviable situation in a market

setting that is always driving toward a market-clearing rate of return.

Further evidence of the existence of a sprinkler guild came from the

checkout lady at the Home Depot. I was buying a sprinkler head and she

said in passing that they didn’t used to carry these things, and the decision

of the manufacturer to supply them in retail got some people mighty upset.

She spoke of the sprinkler repair people as a cult that should be smashed!

Now, does this guild really exist or is it an informal arrangement among

a handful of local suppliers? As best I can tell, here is the guild’s website

(http://www.irrigation.org/default.aspx). The Irrigation Association is

active in:

dangerous words, that come down to the same result: high prices and bad

service.

Why should anyone become certified? “Prestige and credibility

among peers and customers”; “professional advancement opportunities”;

“Enhances the professional image of the industry—your industry.”

I thought I needed a sprinkler repairman but these people want me

to hire a Certified Landscape Irrigation Manager, a CLIM. How do you

become a CLIM? Well you have to send in $400 plus a résumé that includes

an “overview summary of how you plan to meet program criteria:

Two examples of project development to include:

• System design objective

• System budget estimate

• Water source development

• System design drawings: hydraulic, electrical, detail drawings, pump

station

Project specifications:

• General specification

• Installation specification

• Material specification

• Pump station

Two system audits or evaluations to include:

AUDIT

• System performance (uniformity)

• Base schedule

• Recommendations for improvement

EVALUATION

• System performance (uniformity)

• Hydraulic analysis

• Electrical analysis

• Grounding

• Water source

• Product performance

• Recommendations for improvement

Two construction and/or construction management projects:

• Site visit reports

• Drawing of record

• Final irrigation schedule

• Punch lists

Of course they are working with government, federal, state, and local.

They want restrictions of every sort. They want their own Turf and Landscape

Irrigation Best Management Practices or BMP to be the law of the

land. You can read more about this here.

How hip-deep are these people in government? It’s hard to say. But I’m

guessing that local developers, landscapers, builders, and others are intimidated

by all these and are reluctant to challenge their monopoly.

So thank goodness for hardware stores! They are working to bust up

this vicious little guild, to the benefit of the consumer and everyone else.

It means having to stick your fingers in mud and read instruction manuals

and the like but sometimes the defense of liberty requires that you get your

hands a little dirty.

I suspected as much! What the lady at Home Depot called the “sprinkler

repair cult” is an emerging guild seeking privileges and regulations

from the government. That means a supply restriction, high prices, or

another do-it-yourself project. But there is a way around it.

I first began to smell a rat when the automatic irrigation system on my

front yard needed work but I had unusual struggles in trying to find a repair

guy.

The first place I called informed me that they could accept no more clients.

Clients? I just wanted a new sprinkler thing, for goodness sake. I don’t

want to be a client; I want to be a customer. Is there no one who can put on

a new sprayer or stick a screwdriver in there or whatever it needs?

Nope, all full.

The next call was not returned.

The next call ended with the person on the line fearfully saying that

they do landscaping but will have nothing to do with sprinklers or “automated

irrigation systems.” Umm, ok.

The next call seemed more promising. The secretary said they had an

opening on the schedule in three weeks. Three weeks? In that period of

time, my yard will be the color of a brown paper bag.

The next call failed. And the next one. And the next. Finally I was back

to the off-putting secretary. I made the appointment but the guy never came.

Fortunately, in the meantime, a good rain came, and then at regular intervals

for the whole season, and I was spared having to deal with this strangely

maddening situation.

Why all the fuss? We aren’t talking brain surgery here. These are sprinklers,

little spray nozzles connected to tubes connected to a water supply.

Why was everyone so touchy about the subject?

Why did all the power seem to be in their hands, and none in mine?

Must I crawl and beg?

Above all, I wonder why, with most all lawns in new subdivisions sporting

these little things, why oh why are the people who repair them in such

sort supply?

Little did I know that I had stumbled onto the real existence of a most

peculiar thing in our otherwise highly competitive economy: a guild.

It had all the earmarks. If you want your nails buffed, there are thousand

people in town who stand ready. If you want someone to make you

dinner, you can take your pick among a thousand restaurants. If you want to

buy a beer, you can barely go a block without bumping into a merchant who

is glad to sell you one. None of that is true with sprinkler repair.

What does a guild do? It attempts to restrict service. And why? To keep

the price as high as possible. And how? By admitting only specialists, or

supposed specialists, to the ranks of service providers, usually through the

creation of some strange but largely artificial system of exams or payments

or whatever.

Guilds don’t last in a free market. No one can blame producers for trying

to pull it off. But they must always deal with defectors. Even the prospects

of defectors can cause people who might not otherwise defect, to turn

and attempt to beat others to the punch.

There is just no keeping a producer clique together for long when profits

are at stake.

There is also the problem that temporarily successful guilds face: high

profits attract new entrants into the field. They must either join the guild or

go their own way. This creates an economically unviable situation in a market

setting that is always driving toward a market-clearing rate of return.

Further evidence of the existence of a sprinkler guild came from the

checkout lady at the Home Depot. I was buying a sprinkler head and she

said in passing that they didn’t used to carry these things, and the decision

of the manufacturer to supply them in retail got some people mighty upset.

She spoke of the sprinkler repair people as a cult that should be smashed!

Now, does this guild really exist or is it an informal arrangement among

a handful of local suppliers? As best I can tell, here is the guild’s website

(http://www.irrigation.org/default.aspx). The Irrigation Association is

active in:

- Providing a voice for the industry on public policy issues related to

standards, conservation and water-use on local, national and international

levels - Acting as a source of technical and public policy information within

the industry - Raising awareness of the benefits of professional irrigation services

- Offering professional training and certification

- Uniting irrigation professionals, including irrigation equipment manufacturers,

distributors and dealers, irrigation system designers,

contractors, educators, researchers, and technicians from the public

and private sectors.

dangerous words, that come down to the same result: high prices and bad

service.

Why should anyone become certified? “Prestige and credibility

among peers and customers”; “professional advancement opportunities”;

“Enhances the professional image of the industry—your industry.”

I thought I needed a sprinkler repairman but these people want me

to hire a Certified Landscape Irrigation Manager, a CLIM. How do you

become a CLIM? Well you have to send in $400 plus a résumé that includes

an “overview summary of how you plan to meet program criteria:

Two examples of project development to include:

• System design objective

• System budget estimate

• Water source development

• System design drawings: hydraulic, electrical, detail drawings, pump

station

Project specifications:

• General specification

• Installation specification

• Material specification

• Pump station

Two system audits or evaluations to include:

AUDIT

• System performance (uniformity)

• Base schedule

• Recommendations for improvement

EVALUATION

• System performance (uniformity)

• Hydraulic analysis

• Electrical analysis

• Grounding

• Water source

• Product performance

• Recommendations for improvement

Two construction and/or construction management projects:

• Site visit reports

• Drawing of record

• Final irrigation schedule

• Punch lists

Of course they are working with government, federal, state, and local.

They want restrictions of every sort. They want their own Turf and Landscape

Irrigation Best Management Practices or BMP to be the law of the

land. You can read more about this here.

How hip-deep are these people in government? It’s hard to say. But I’m

guessing that local developers, landscapers, builders, and others are intimidated

by all these and are reluctant to challenge their monopoly.

So thank goodness for hardware stores! They are working to bust up

this vicious little guild, to the benefit of the consumer and everyone else.

It means having to stick your fingers in mud and read instruction manuals

and the like but sometimes the defense of liberty requires that you get your

hands a little dirty.

Saturday, November 10, 2012

How Free Is The "Free Market"?

Mojo is winding down his interest in his blog. I am going to re-post a few of my posts their over here, for posterity. I may want to revisit the subjects.

In an attempt to get more of you to read Jeffery Tucker's excellent books, Bourbon for Breakfast and Its A Jetson's World, I'm going to copy a chapter from the former here.

Read chapters 24-28 of Bourbon for Breakfast (starts at page 114) for the reasons for why he'd be fine with my copying his work here. (Summary: no one owns ideas, please take my ideas as yours)

Chapter 18 (page 88)

of which seems to appear in a book, magazine, or newspaper every

few weeks for as long as I’ve been reading public commentary on economic

matters:

Now, a paragraph like this one printed in the New York Times opinion

section on December 30, 2007—in an article called “The Free Market: A

False Idol After All?”—makes anyone versed in economic history crazy

with frustration. Just about every word is misleading in several ways, and

yet some version of this scenario appears as the basis of vast amounts of

punditry.

The argument goes like this:

Until now we’ve lived in a world of laissez-faire capitalism, with government

and policy intellectuals convinced that the market should rule no matter

what. Recent events, however, have underscored the limitations of this

dog-eat-dog system, and reveal that simplistic ideology is no match for a

complex world. Therefore, government, responding to public demand that

something be done, has cautiously decided to reign in greed and force us all

to grow up and see the need for a mixed economy.

All three claims are wrong. We live in the 100th year of a heavily regulated

economy; and even 50 years before that, the government was strongly

involved in regulating trade.

The planning apparatus established for World War I set wages and

prices, monopolized monetary policy in the Federal Reserve, presumed

first ownership over all earnings through the income tax, presumed to know

how vertically and horizontally integrated businesses ought to be, and prohibited

the creation of intergenerational dynasties through the death tax.

That planning apparatus did not disappear but lay dormant temporarily,

awaiting FDR, who turned that machinery to all-around planning during

the 1930s, the upshot of which was to delay recovery from the 1929

crash until after the war.

Just how draconian the intervention is ebbs and flows from decade to

decade, but the reality of the long-term trend is undeniable: more taxes,

more regulation, more bureaucracies, more regimentation, more public

ownership, and ever less autonomy for private decision-making. The federal

budget is nearly $3 trillion per year, which is three times what it was in

Reagan’s second term. Just since Bush has been in office, federal intervention

in every area of our lives has exploded, from the nationalization of airline

security to the heavy regulation of the medical sector to the centralized

control of education.

With “free markets” like this, who needs socialism?

So, the first assumption, that we live in a free-market world, is simply

not true. In fact, it is sheer fantasy. How is it that journalists can continually

get away with asserting that the fantasy is true? How can informed writers

continue to fob off on us the idea that we live in a laissez-faire world that can

only be improved by just a bit of public tinkering?

The reason is that most of our daily experience in life is not with the

Department of Labor or Interior or Education or Justice. It is with Home

Depot, McDonald’s, Kroger, and Pizza Hut. Our lives are spent dealing

with the commercial sector mostly, because it is visible and accessible,

whereas the depredations of the state are mostly abstract, and its destructive

effects mostly unseen. We don’t see the inventions left on the shelf, the

products not imported due to quotas, the people not working because of

minimum wage laws, etc.

Because of this, we are tempted to believe the unbelievable, namely

that government serves the function only of a night watchman. And only by

believing in such a fantasy can we possibly believe the second assumption,

which is that the problems of our society are due the to the market economy,

not to the government that has intervened in the market economy.

Consider the housing crisis. The money machine called the Federal

Reserve cranks out the credit as a subsidy to the banking business, the bond

dealers, and the big-spending politicians who would rather borrow than

tax. It is this alchemic temple that distorts the reality that credit must be

rationed in a way that accords with economic reality.

The Federal Reserve embarked on a wild credit ride in the late 1990s

that has dumped some $4 trillion in new money via the credit markets, making

expansion of the loan sector both inevitable and unsustainable. At the

same time, the federal bureaus that manage and guarantee the bulk of mortgages

have ballooned beyond belief. The popularity of subprime mortgages

is the tip of a massive but buried debt mountain—all in the name of achieving

the “American dream” of home ownership through massive government

intervention.

Say what you want to about this system, but it is not the free market at

work. Indeed, the very existence of central banking is contrary to the capitalist

ideal, in which money would be no different from any other good:

produced and supplied by the market in accord with the moral law against

theft and fraud. For the government to authorize a counterfeiter-in-chief is a

direct attack on the sound money system of a market economy.

Let’s move to the third assumption, that government intervention can

solve social and economic problems, with global warming at the top of the

heap. Let’s say that we remain agnostic on the question of whether there is

global warming and what the cause really is (there is no settled answer to

either issue, despite what you hear). The very idea of putting the government

in charge of changing the weather of the next 100 years is another

notion from fantasy land.

The point about complexity counts against government intervention,

not for it. The major contribution of F.A. Hayek to social theory is to point

out that the social order—which extends to the whole of the world—is far

too complicated to be managed by bureaus, but rather depends on the

decentralized knowledge and decisions of billions of market actors. In other

words, he gave new credibility to the insight of the classical liberals that the

social order is self-managing and can only be distorted by attempts to centrally

plan. Planning, ironically, leads to social chaos.

You don’t have to be a social scientist to understand this. Anyone who

has experience with public-sector bureaucracies knows that they cannot do

anything as well as markets, and however imperfect free markets are, they

are vastly more efficient and humane in the long run than the public sector.

That is because free markets trust the idea of freedom generally, whereas

other systems imagine that the men in charge are as omniscient as gods.

In one respect, the New York Times is right: there is always a demand for

economic intervention. The government never minds having more power,

and is always prepared to paper over the problems it creates. An economy

not bludgeoned by powerful elites is the ideal we should seek, even if it has a

name that is wildly unpopular: capitalism.

In an attempt to get more of you to read Jeffery Tucker's excellent books, Bourbon for Breakfast and Its A Jetson's World, I'm going to copy a chapter from the former here.

Read chapters 24-28 of Bourbon for Breakfast (starts at page 114) for the reasons for why he'd be fine with my copying his work here. (Summary: no one owns ideas, please take my ideas as yours)

Chapter 18 (page 88)

How Free Is the "Free Market"?

See if you can spot anything wrong with the following claim, a versionof which seems to appear in a book, magazine, or newspaper every

few weeks for as long as I’ve been reading public commentary on economic

matters:

The dominant idea guiding economic policy in the United

States and much of the globe has been that the market is

unfailingly wise….

But lately, a striking unease with market forces has entered

the conversation. The world confronts problems of staggering

complexity and consequence, from a shortage

of credit following the mortgage meltdown, to the threat

of global warming. Regulation … is suddenly being

demanded from unexpected places.

Now, a paragraph like this one printed in the New York Times opinion

section on December 30, 2007—in an article called “The Free Market: A

False Idol After All?”—makes anyone versed in economic history crazy

with frustration. Just about every word is misleading in several ways, and

yet some version of this scenario appears as the basis of vast amounts of

punditry.

The argument goes like this:

Until now we’ve lived in a world of laissez-faire capitalism, with government

and policy intellectuals convinced that the market should rule no matter

what. Recent events, however, have underscored the limitations of this

dog-eat-dog system, and reveal that simplistic ideology is no match for a

complex world. Therefore, government, responding to public demand that

something be done, has cautiously decided to reign in greed and force us all

to grow up and see the need for a mixed economy.

All three claims are wrong. We live in the 100th year of a heavily regulated

economy; and even 50 years before that, the government was strongly

involved in regulating trade.

The planning apparatus established for World War I set wages and

prices, monopolized monetary policy in the Federal Reserve, presumed

first ownership over all earnings through the income tax, presumed to know

how vertically and horizontally integrated businesses ought to be, and prohibited

the creation of intergenerational dynasties through the death tax.

That planning apparatus did not disappear but lay dormant temporarily,

awaiting FDR, who turned that machinery to all-around planning during

the 1930s, the upshot of which was to delay recovery from the 1929

crash until after the war.

Just how draconian the intervention is ebbs and flows from decade to

decade, but the reality of the long-term trend is undeniable: more taxes,

more regulation, more bureaucracies, more regimentation, more public

ownership, and ever less autonomy for private decision-making. The federal

budget is nearly $3 trillion per year, which is three times what it was in

Reagan’s second term. Just since Bush has been in office, federal intervention

in every area of our lives has exploded, from the nationalization of airline

security to the heavy regulation of the medical sector to the centralized

control of education.

With “free markets” like this, who needs socialism?

So, the first assumption, that we live in a free-market world, is simply

not true. In fact, it is sheer fantasy. How is it that journalists can continually

get away with asserting that the fantasy is true? How can informed writers

continue to fob off on us the idea that we live in a laissez-faire world that can

only be improved by just a bit of public tinkering?

The reason is that most of our daily experience in life is not with the

Department of Labor or Interior or Education or Justice. It is with Home

Depot, McDonald’s, Kroger, and Pizza Hut. Our lives are spent dealing

with the commercial sector mostly, because it is visible and accessible,

whereas the depredations of the state are mostly abstract, and its destructive

effects mostly unseen. We don’t see the inventions left on the shelf, the

products not imported due to quotas, the people not working because of

minimum wage laws, etc.

Because of this, we are tempted to believe the unbelievable, namely

that government serves the function only of a night watchman. And only by

believing in such a fantasy can we possibly believe the second assumption,

which is that the problems of our society are due the to the market economy,

not to the government that has intervened in the market economy.

Consider the housing crisis. The money machine called the Federal

Reserve cranks out the credit as a subsidy to the banking business, the bond

dealers, and the big-spending politicians who would rather borrow than

tax. It is this alchemic temple that distorts the reality that credit must be

rationed in a way that accords with economic reality.

The Federal Reserve embarked on a wild credit ride in the late 1990s

that has dumped some $4 trillion in new money via the credit markets, making

expansion of the loan sector both inevitable and unsustainable. At the

same time, the federal bureaus that manage and guarantee the bulk of mortgages

have ballooned beyond belief. The popularity of subprime mortgages

is the tip of a massive but buried debt mountain—all in the name of achieving

the “American dream” of home ownership through massive government

intervention.

Say what you want to about this system, but it is not the free market at

work. Indeed, the very existence of central banking is contrary to the capitalist

ideal, in which money would be no different from any other good:

produced and supplied by the market in accord with the moral law against

theft and fraud. For the government to authorize a counterfeiter-in-chief is a

direct attack on the sound money system of a market economy.

Let’s move to the third assumption, that government intervention can

solve social and economic problems, with global warming at the top of the

heap. Let’s say that we remain agnostic on the question of whether there is

global warming and what the cause really is (there is no settled answer to

either issue, despite what you hear). The very idea of putting the government

in charge of changing the weather of the next 100 years is another

notion from fantasy land.

The point about complexity counts against government intervention,

not for it. The major contribution of F.A. Hayek to social theory is to point

out that the social order—which extends to the whole of the world—is far

too complicated to be managed by bureaus, but rather depends on the

decentralized knowledge and decisions of billions of market actors. In other

words, he gave new credibility to the insight of the classical liberals that the

social order is self-managing and can only be distorted by attempts to centrally

plan. Planning, ironically, leads to social chaos.

You don’t have to be a social scientist to understand this. Anyone who

has experience with public-sector bureaucracies knows that they cannot do

anything as well as markets, and however imperfect free markets are, they

are vastly more efficient and humane in the long run than the public sector.

That is because free markets trust the idea of freedom generally, whereas

other systems imagine that the men in charge are as omniscient as gods.

In one respect, the New York Times is right: there is always a demand for

economic intervention. The government never minds having more power,

and is always prepared to paper over the problems it creates. An economy

not bludgeoned by powerful elites is the ideal we should seek, even if it has a

name that is wildly unpopular: capitalism.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)